Stagflation and End-of-Policy-Days

The world economy is broken, and not to be restored quickly or easily. Policy-initiatives will, needs must, be aimed at fostering elements of autarkic national independence. International flows of goods, services, labour and capital will wither, and national governmental policy interventions will narrow the space within which the market will be allowed to work its magic. Getting reliable supplies of food and power will be categorical imperatives which will over-ride projects soon to be discovered to be vanities. The fallout hits first and hardest in Europe, but will necessarily spread around the rest of the world.The architecture of our times crumbled this week, and it will take years, possibly decades, before a new modus vivendi compatible with progress towards widespread prosperity is realised. In effect, Russia’s disastrous invasion of Ukraine, coupled with Ukraine discovering beyond doubt its modern foundational national myth, means the de-globalisation which has been evident for the best part of a decade is thrown into warp-drive hyper-speed. Separately, the supply chain disruptions which are at the heart of current inflation have been escalated in ways which are probably even more extreme than the Oil Crisis of the 1970s.

It is, I suppose, possible that the next couple of weeks will allow a post-Putin Russia to find a way to restore their membership of the recognisably investible community of economic counterparties. But it is just as likely that the despot will start throwing nukes or chemical/bioweapons around in a way which ushers in a new Dark Age for all of us.

The immediate future for Europe, and probably everywhere else as well, is stagflation, as the rise in commodity prices (energy, food, industrial commodities) ‘taxes’ households and businesses into a contraction which can do little quickly to deal with the global sources of inflation. On the surface, stagflation’s rebirth might seem merely the result of several ‘black swan’ accidents happening at once. But the severe difficulties it raises for policy-makers also signals that stagflation is a phenomenon which accompanies the exhaustion of prevailing economic policy nostrums and approaches.

Last year, in ‘The Wrong Super-Cycle’ I wrote: ‘The real super-cycle the current [commodity] price rises are telling us about is the belated end of the financial industry super-cycle which was initiated when Paul Volcker arrived at the Fed determined to tackle inflation. The result was a generations-long uninterrupted bond bull market which reached its natural peak around the turn of the century, and extended through to around 2010, ironically by responses to the multiple crises actually generated by the end of the cycle. The final extension has been granted only by the utterly unprecedented impact of a global pandemic, which has left central banks as the main supporters of government bond markets. The last buyer is in mid-buying climax.’

But never in my worst nightmares did I consider the end would come so abruptly and violently.

The quandary for policymakers is obvious:

- raise interest rates to crush inflation, and you trigger a dramatic recession with an accompanying financial-market meltdown;

- keep monetary policy super-accommodating, and watch ‘cost-push’ inflation morph into the full wage/price spiral of money-value destruction.

Within the currently accepted framework for economic-policymaking, this dilemma cannot be finessed. The result will be a make-over of the policymaking framework, but who knows how long it will take us to get there?

The danger is that the immediate response will be to re-play the moves which ended the last bout of stagflation. But because our contemporary set of accepted economic truths and policy-nostrums were born directly of that stagflationary experience and have now reached their own stagflationary end-point, doubling down on those nostrums would be – must be – the wrong response.

Stagflation – Last Time

It pays to remember the circumstances which ignited stagflation the last time. I shall use the British experience as the exemplar.

Since the early 1960s, the policy watchword was ‘demand management’, which essentially meant expanding the fiscal deficit in order to make up any expected or actual shortfall in private demand – and thus to ensure GDP growth, and employment, was maintained. The corollary was national economic planning implemented by industrial and labour policy. In particular, this meant that the unions were involved in setting up the national plan, and helping with its implementation via keeping workers’ demands under control even as inflation rose. In practice, it was a recipe for keeping political struggle contained within the walls of No10, and things being settled through deals we would now see as corrupt. Industrial inefficiency was masked and indulged by industrial and labour policy. This was unavoidably noticeable in those swathes of industry which were under union/government control/influence, but the widespread regime of labour subsidies meant it was widespread even in notionally private industries.

The underlying deal had been unravelling quietly for some time when the oil shock hit in late 1973. It was large enough to derail government/union deals, with ‘wildcat’ pay-strikes blossoming as people tried to maintain their standard of living in the face of rampant inflation.

The policy board was bare, and increasingly bereft attempts to tamp down the solution whilst buying off discontent led to Britain’s bankruptcy in 1976. The IMF’s rescue package and an interim attempt at austerity ultimately produced the ‘winter of discontent’ where, famously, no rubbish was collected, the dead went unburied, and the lights went out. Bliss was it in those days to be alive.

It did, however, herald the way for the eventual overthrow of the ‘demand management’ economic policy approach, and the arrival of a new policy-settlement. It has subsequently been christened the arrival of ‘neo-classical’ economics, but, of course, that hardening of the academic arteries was achieved only in hindsight to describe a partial and chaotic rebuilding of Britain’s entire political economy. At the time, the policy solution was seen to have two main components. First, inflation was broken by massively ramping interest rates and controlling money supply, at the cost of massive unemployment. Second, and equally important, the ‘unions were broken’, and consequently the ability of workers to fight for higher wages was destroyed. (Revealing, among other things, how ludicrous is it to believe that wages are set simply by supply and demand, rather than by adjusting the political/economic setup.)

Stagflation – This Time

It should be plain that the stagflation we are about to endure is breaking out in circumstances utterly unlike those which fostered it in the 1970s.

This time, the stagflation comes about because of broken supply chains extending well beyond oil and gas, as the age of globalisation is dismantled across a shockingly broad landscape, encompassing not just oil but many industrial commodities, food, labour, investment and financial flows.

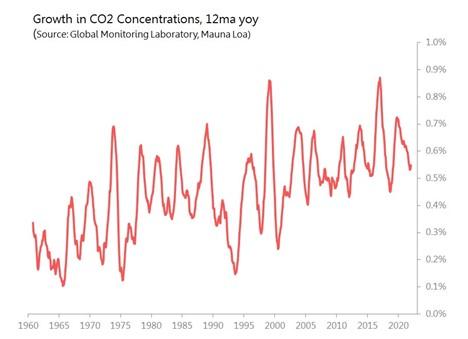

On top of which, of course, the West has also opted for various restrictions on activity (consumption, investment, saving) in its Green Theatre productions, featuring its absurdist ‘net zero’ pageant. The problem is that this Green Theatre has done nothing substantial to address a genuinely serious problem, is doing nothing to address it, and will/can do nothing to address it. It is not that the problem is not serious, it is that Green Theatre solutions are not. We may lament it, but should not deny it: the pace of rise in atmospheric CO2 concentrations has not even been slowed.

The current threat of stagflation has nothing to do with labour militancy, and comes at a time when monetary policy and fiscal policy are both extremely extended, so have little scope for being accommodating. And since the current inflation is not fundamentally about ‘too much demand’, it is doubtful that anything but a really, really deep recession would chase inflation away.

Moreover, if the current threat of stagflation is not fundamentally about excess but rather a sudden and unavoidably irreparable collapse in supply-chains and supply-systems, neither fiscal nor monetary tightening would be an efficient or even logical way to deal with the problem.

Stagflation 2020s – Possible Policy Approaches

What, then, would be a sensible approach to stagflation this time? Quite simply, because the underlying problem is a lack of supply, the policy emphasis should be on accepting/encouraging lowered consumption and using the savings surplus generated to finance sufficient investment spending to avoid recession. Only a savings/investment led growth mix can help us out of this stagflation. The investment spending will be needed in order to deal with the various supply-shortage issues which we now encounter. Most obviously, massive investment will be needed to overhaul energy infrastructures in the short (gas, fracking, coal) and longer terms (small modular nuclear reactors). Government subsidies will probably be needed to blunt the impact of rocketing fertiliser prices on food-production. But this increased investment spending, which will necessarily involve substantial public sector involvement, will need to be financed as far as possible from household and business sector savings, rather than simply central bank largesse.

An economic model which accepts lower consumption spending in the short term, but offsets this through broad-scale policy efforts to encourage investment spending, may in time limit the damage to GDP growth whilst discovering a way out of the trap of stagflation.

If this involves such policy throwbacks as an active industrial policy and an active attempt to encourage the public (that is to say, households, not banks) to buy government debt, then so be it. A throwback it is. But so is a Cold War and an Oil Crisis all in one.

First published on Michael Taylor’s substack, Coldwater Economics, March 6th 2022.

There are plenty of people out there who say that much of the current bout of inflation is brought on buy the QE that the BoE engaged in during the pandemic. Is that entirely wrong? If it is partially right, wouldn’t monetary tightening provide at least some help in addressing inflation?

Meanwhile, less consumption spending and more investment is surely a good thing for our economy…but less consumption spending is a tough sell politically. How on earth do you get the political mandate to do it?

This Country is crying out for alternative leadership not offer by the 3 failed Old parties the sdp could be that alternative Government Johnson is a fraud and Starmer is woeful